A Conversation with Special Exhibitor Izzy Cho

1. What are your earliest memories of art? How did you become an artist yourself?

My earliest memories of art are from my mother. I remember her staying up late to finish one of her paintings or the both of us taking ceramics classes together. It really was not a surprise to either of us that I ended up wanting to be a working artist.

Initially, I used art as a way to understand why I often felt isolated and out of place before I had even heard of the term “diaspora”. For a while I didn’t have the language or research to help contextualize my experiences, so instead I created spaces for myself through sculpture or installation. It was a way to make myself safe environments that were bespoke and still described the liminality I constantly felt.

Now, I feel like I transitioned to using art to learn more about my culture in a personal and contemporary context that makes me happy and my work happy. A lot of my early projects felt a bit funereal, mournful, and wistful when describing my relationship with my culture/identity, but now it’s very celebratory and makes fun of itself more! Haha.

2. Your exhibit is titled “Gift Giving.” Can you tell us why you chose that name?

Gift giving is delightful, magical, and generative which I visually represent through repetition of imagery, burgeoning blossoms and sparkles, etc. The connection of gift giving and magic is further compounded within the context of literary mythology and superstition: Forbidden fruit, magic fabrics, or incredibly practical objects.

I also think about gift giving a lot within a Korean American context; the act of giving a gift alludes to specific systems of politeness, traditional superstitions, and class structures. Although these cultural nuances exist through cultural persistence and survival, I can’t deny the role capitalism has since many traditions and cultural items persist through systematic monetization. Also, transnational sharing, trade, and globalization is in part why Korea is such a prominent global pop cultural power right now.

Most of the imagery and concepts within my work are inspired by gestures of kindness, sharing, and literal gifts given to me. These moments, as well as my mother being my cultural filter, are the way I learned about my heritage- which is a formative gift in itself.

3. Your work is very intricate and unique. What is your process for creating this work?

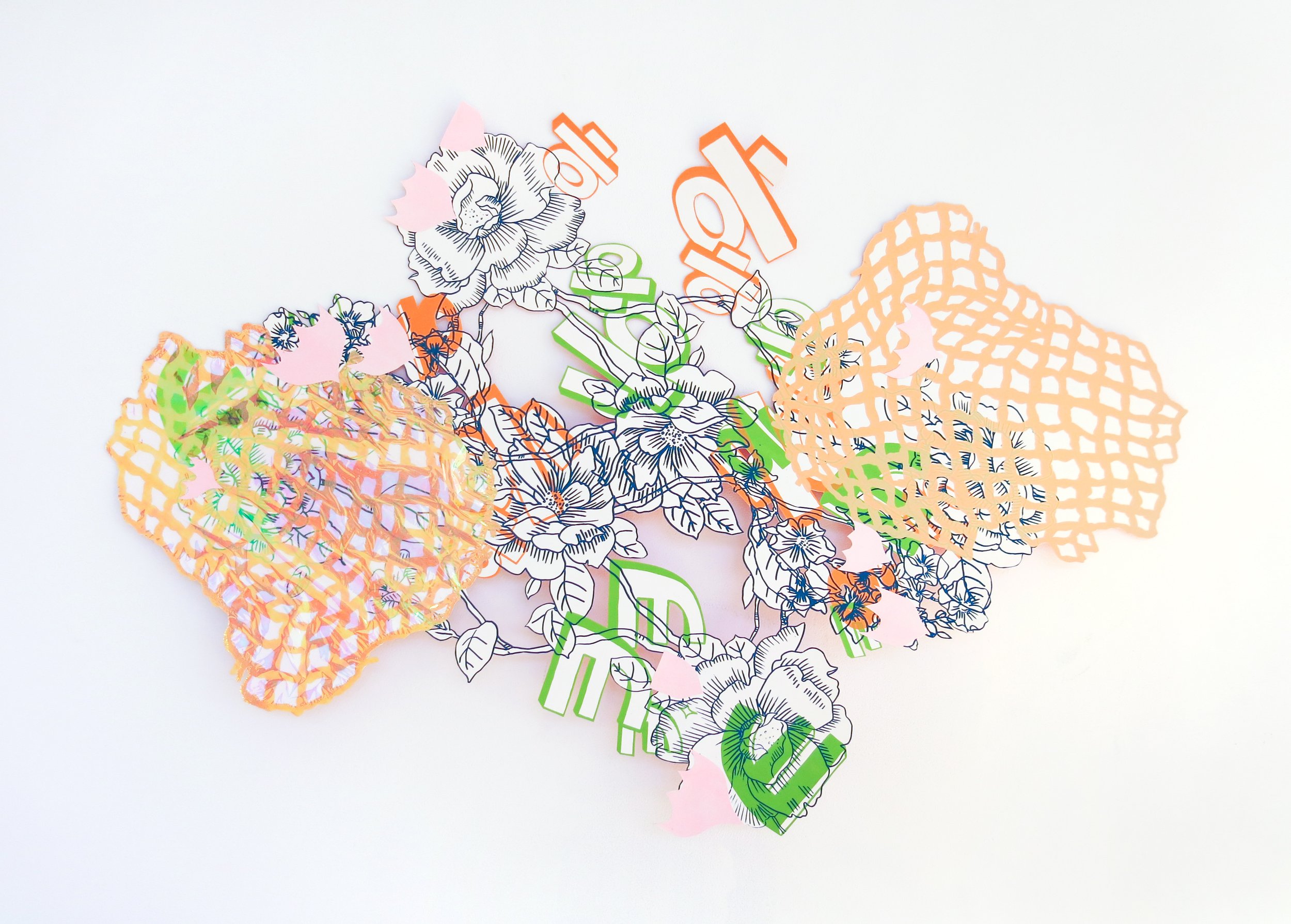

It’s scarily easy for me to go down a rabbit hole or be frozen by minute decision-making, so I’ll often give my set of rules or “equations” to execute in order to be more efficient. For instance, with my In Plain Sight screenprint series, I gave myself the equation of 2 screenprinting layers + 2 drawing elements + 2 collage materials. Sometimes, people are surprised by how dry my process actually is in comparison to the organic and playful movement within my work. However, I also think this process means having trust that the imagery and material will create enough dimension together, just as long as I facilitate a plane for them to interact on.

Conceptually speaking, I’ve been focusing a lot on Korean superstition and incorporating aspects from rituals and spiritual objects. There’s been a lot of study of shapes and illustrations as I look through the books my mom and sister give me. Also, just a lot of rumination on the lessons my mom taught me; sometimes quirky (“don’t cut your toenails at night!”) but often thoughtful and based in a game of “generational telephone”, which is just my way of describing how traditions are passed down over time. So I guess this equation would be Something From Research + Something From My Mom + Something From Myself.

4. You recently graduated from the SAIC. What was the focus of your work there and how did your work change as a result of that experience?

I graduated with an MFA in Printmedia at SAIC! Although, I probably made more sculptural objects than prints during my time there. Ultimately, I think I learned to trust my intuition more. I realized that my personal preferences are valid! The colors, shapes, and textures I'm naturally attracted to are all a part of my cultural framework which are informed by my distinct diasporic experiences and the relationships I make with others.

5. Some of your work is not only 3-D, but also allows for a unique, 360 degree viewing experience. Can you tell us a bit more about what has inspired that?

I’ve always been inspired by installation art, particularly by Korean contemporary artists such as Suh Do Ho and Kimsooja. To be honest, those two are probably the most well-known Korean transnational artists to reference, but I can’t help it! Their work was really foundational for me and informed my desire to make my practice more bodily engaging beyond seeing it on a single plane. This desire led me to join many other artists in expanding the field of printmaking.

6. Where do you see your work going from here?

Being Korean American goes beyond image and iconography so I want to push myself to make my work more immersive and sensorial. Maybe through large scale installations, sound, or even smell. Going along with that, much of my work relies on visual gravity in order to imply movement so I think it would be quite playful to actually add literal movement with motors or fans.

I would love for my work to develop more intellectual and conceptual depth through research. I’m making eye contact with some new books on my desk right now (Our Aesthetic Categories by Sianne Ngai, Ornamentalism by Anne Annlin Chen, and Best Letters from Asian Americans in the Arts edited by Christopher K. Ho and Daisy Nam, to name a few). And, of course, I should call my mom more since she is a large part of my work already.